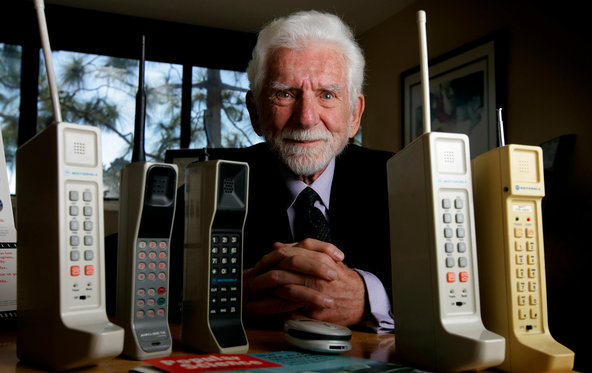

Martin Cooper, The Father of Cellphone Urges For Tech Solutions For Spectrum Efficiencies

Martin Cooper, the former vice president of Motorola who helped create the first working cellphone, has been saying for some time that technology is the solution to dealing with the ever-rising demand for wireless data capacity. Now a presidential advisory committee agrees with him, urging President Obama to adopt technologies that would use radio spectrum more efficiently. Wireless carriers argue that they need more spectrum, not just better-managed spectrum.

Martin Cooper, the former vice president of Motorola who helped create the first working cellphone, has been saying for some time that technology is the solution to dealing with the ever-rising demand for wireless data capacity. Now a presidential advisory committee agrees with him, urging President Obama to adopt technologies that would use radio spectrum more efficiently. Wireless carriers argue that they need more spectrum, not just better-managed spectrum.

An edited transcript of an interview with Mr. Martin Cooper follows.

Q.

Spectrum-sharing technology — is this what you’ve been talking about the entire time?

A.

The committee is proposing the approach that I’ve been advocating for over 20 years. The magic that makes all of this work is already known. It’s several technologies that, put together, are called dynamic spectrum access.

The high-level principle is simple. Today, almost all of the spectrum is unused when one thinks about time, geographic area and frequency band. For example, the F.C.C. assigns a radio channel to an operator. A person makes a cellphone call on that channel. The channel is reserved for that person over the entire area of the cell and for the duration of the call whether he is speaking or not. The entire area covered by a cell station is flooded with the energy from the one call. Suppose the information in the call could be transmitted directly from the person to the cell station. Then many people could talk on their phone in the coverage area of each station without interfering with each other. Further, when the person is not talking, others could use the channel.

The technology that lets many people use the same radio channel at the same time is called smart antenna technology or adaptive array technology or interference mitigation. This technology uses computer processors to take the signals from multiple antennas at each location and sorts the various signals out so they don’t interfere with each other.

Add to that the technology the committee refers to, and someone desiring to make a call has a way of detecting whether there is some free radio spectrum, a free radio channel, available in his location that will not interfere with other people.

The technology that senses whether a channel is available is known as cognitive radio. The technology that allows the cellular radios to use any of a large number of channels is called software-defined radio, or frequency-agile radio.

Smart antenna technology has been available for almost 20 years but is not yet used by cellular operators. Cognitive radio technology is still in the early stages of development but could be available in five to 10 years. All radios today are software defined, but their agility is not yet adequate; that will take five years or longer.

The bottom line is, yes, it’s all technology that makes the use of the spectrum more efficient. I’ve been literally doing that for my whole career when I started at Motorola in 1954. The issue was, we didn’t have enough spectrum for two-way radios. We didn’t have enough spectrum for the police departments, the taxicabs and the plumbers; we were struggling to make our two-way radios more efficient, which we did with all kinds of technologies back in the 1950s.

It’s a never-ending battle. People are mobile. They move around, and anytime they want to communicate, if you tie them to the wall or the wires, you’re restricting them, you’re infringing on their freedom. The more we learn about new communications, the more capacity we need, and that is going to keep going on forever. That’s been happening since radio was invented, and that’s going to keep going. The only way to solve that is by new technology. You can’t create new spectrum.

Q.

The report concludes that the radio spectrum could be used as much as 40,000 times as efficiently as it is currently, and increase capacity a thousandfold. That sounds dramatic. Is it feasible?

A.

Doubling every two and a half years is Cooper’s Law. You don’t have to double very much to get to 40,000. When they say 40,000 times, that’s not going to happen immediately. It’s going to take 20 years. That’s a million times more spectrum. It’s a matter of time: None of these things happen instantaneously. It’s going on every 10 years. Each time you put in new technology you get a big jump. The immediate jump they can get is 10 or 20 times.

You combine smart antennas, cognitive radio, and the processors get better — all of these techniques require computer processors. As the processors get more powerful, the more efficient they get and they’re able to do more spectrally efficient techniques. It’s all continual. Little by little you add technologies, you improve the processing, you try a different technique and you get incremental improvement.

Q.

The carriers wonder whether the cognitive-radio technology described in the report is commercially available or scalable. What do you know about it? How does it work?

A.

It’s true, it’s not commercially available. The biggest problem I have in these committees is, you’ve got a bunch of lawyers and lobbyists and they keep talking about cognitive radio, which I would say is 10 years away. This interference mitigation with smart antennas, these are systems that have been operating for 10 years that are 20 times more efficient than what the carriers are doing today. But cognitive radio is in development, and by all means it’s feasible. But it’s a red herring. It’s feasible and can be used only in certain bands right now because the law doesn’t permit it.

Cognitive radio is really simple. An example: You have two television stations, one in Philadelphia and one in New York. Here’s a guy who wants to send a two-way radio transmission somewhere in between those two in New Jersey. He takes a receiver and he sniffs. He tries to hear if there’s any television signal there. If there’s no signal there he’ll determine he can send a signal. The cognitive part is he’s listening, to be aware of whether somebody is in the spectrum, to know whether you’re going to interfere with the other guy sharing the spectrum between two different services.

No. 1, you’ve got a technical problem — we haven’t figured that out yet. The second is the law doesn’t provide for that, so the law has to be changed. Cognitive radio is one example of why it’s the magic word among the lobbyists and lawyers who have no idea what it is, and it doesn’t exist yet.

It’s a matter of what has been demonstrated. In a dozen countries there are systems using smart antennas that are at least 20 times more spectrum efficient. Why aren’t we doing that? We’ve got this new system, LTE, and that has the capability of doing it, but nobody is using it yet.

Q.

The wireless industry says that even if this technology pans out, they still want the government to “clear” additional spectrum for them. Why would they need more?

A.

I keep repeating this: How can 20 percent more spectrum — which is in their wildest dreams as much as they’re ever going to get — how can that solve the problem when you need 20 times more spectrum? You can’t. They’ve got to be pushing harder on technology. They’re not using technology that exists today and was demonstrated 10 years ago.

Q.

We know who the winners would be if spectrum sharing came to fruition. Who would be the losers?

A.

The big winner is the public. The object is not only spectrum, it’s getting the cost down. The public interest is low-cost access to spectrum. Everybody can benefit from it. As you know, they [the carriers] stopped doing all-you-can-eat. Even the people providing all-you-can-eat charge a lot of money for it. The objective is to have very low-cost spectrum.

My belief is that everybody wins. It’s competition. The more competition you have, the harder people fight to serve your customers, and the lower the costs get and the more service they get. How can you get more fundamental than that?

Q.

The presidential committee’s proposal is a big step, but what’s missing from it?

A.

The only place I’ve been urging the government to act is, they ought to be putting more pressure on existing users of the spectrum to use the spectrum more effectively. There are ways of measuring how well an operator or a broadcaster, how efficiently they’re using it. And if you can measure it, you can tell them, hey, we the public own the spectrum. You don’t own it, you just license it. If you don’t use it efficiently, we’re going to take it back. That’s what they should be doing.

The amazing thing is there’s so much technology that’s becoming available, it’s not as though you have to imagine that maybe something is going to happen. The technology that we already know about can be the short-term solutions. We know the technologies that we’re working on that will be the next generation. I try to protect these future technologies — I have a technology road map that goes on to way beyond my lifetime of things that are on the schedule that we’ve got to be working on. So it all fits together very neatly if we get around the politics and the self-interest.